016 — Soft Purring in the Dark of Night

Yesterday I huffed up the stairs, lugging a 20-pound sack of kitty litter to our second-floor apartment. It was something I hadn't done in about four years.

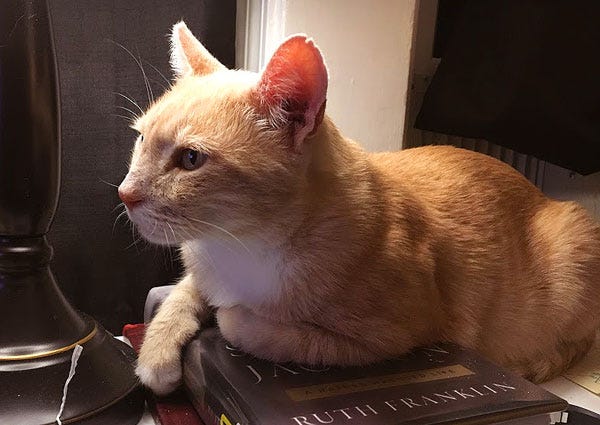

After years of mourning the loss of the last of our original three cats, we finally adopted another one. We've named him Carlitos.

To be honest, I wasn't sure we'd ever have another pet. People who have never had pets — or who have some fundamental thing missing from their souls — don't understand it, but the feeling of loss when a pet dies is real. It's deep and painful. Our love for our cats was profound, and watching the life slowly slip away from them broke my heart. Sandy was beyond sad, with a sense of unearned guilt because, somehow, we couldn't make our cats live forever. Because the 18 and 19 years they gave us just wasn't enough.

It's hard not to be selfish when it comes to the time you have with your loved ones.

Peggy was the first to come to us. Sandy and I were still dating, and I hadn't even moved in yet. My sister called me, saying, "Hey, do you think Sandy wants a cat?" Her friend had found a tiny gray and white kitten lying literally in a gutter. The kitten was sick, my sister said. She thought the cat would probably make it, but ...

Sandy took the kitten anyway, and named the first pet of her own Peggy, after a crazy bird-thing on Mexican TV. Peggy was a fuzzball, a shock of fur with needle-sharp claws and eyes puffed shut with illness, meowing faint but steady protest. It fell to me to give her the medicine she needed, which led to the invention of a method that was half squat, half wrestling move just to keep the bloodshed to a minimum. She bounced back like most youth do — quickly and completely — and with time went from holy terror to queen of the household. I would give her any medicine she needed for the rest of her life, including what she needed to fight the thyroid disease that eventually took her from us at age 18.

Next came Pancho. He came from one of two litters of cats born on the family rancho of a newspaper colleague of ours. His littermates went quickly among folks in the newsroom, and when Charlie brought Pancho to us sight unseen one mid-morning before work, we saw why he'd been the last cat to be picked. Small, golden, and with lunacy shining from his cornflower-blue eyes, Pancho was easily the ugliest cat I'd ever seen. When Sandy came into the bedroom and plopped him on my chest by way of introduction, the first thing I actually said was, "That's the ugliest cat I've ever seen." He was all head, an oversized noggin wobbling on a noodle of a neck, and the first thing he did was attack my face. He was clumsy, thrown off-balance by the gravity his brainpan generated, and he paired this with a natural tendency for non-stop mischief.

In true ugly duckling fashion, Pancho's body caught up to his head and he became, frankly, beautiful. One of the most beautiful cats I've ever known. He was sweet, and loving, and wanted nothing more than to drape you with his affection. Even on his last day, with cancer eating away at his jaw, he meowed, jumped onto my chest so I could cradle him, and purred. He was 19.

Rizzo was the last to join us, the classic story of a young, single mother just looking for a place to stay. We first saw her behind a hedge in the front yard of the house we owned at the time. A black and brown Siamese, she glared at me, cross-eyed, from the leafy shadows. I ignored her (if you want to get a cat's attention, blow them off completely and they won't be able to resist trying to figure out what's wrong with you). I went into the house, found a couple of plastic tubs, and filled one with kibble and the other with water. I took them outside, shook the dry food while clicking my tongue, and put it all down where she could see it. I went back into the house and immediately went to the window to spy on her Peeping Tom-style through the curtains. I kept this up for more than a week, finally getting to the point where Rizzo would come to me when I fed her, meowing and rubbing against my jeans.

Finally, she tried to come into the house, meowfing her demand to become an inside cat. But we'd noticed something — this cat was pregnant. "No," I told her, as she looked at me like a feline Marty Feldman. "Go have your babies and then come back." Rizzo was the smartest of the three, and as if understanding me, she disappeared for a few weeks and then came back, no longer preggo. There were, however, a batch of feral kittens running around the backyard. "OK," I said, because a deal's a deal, and I held the door open for her as she strolled in. Until she died at 18 due to kidney disease, she never showed any interest in going back outside, ever. She was content to lay in your lap for hours instead, if you'd let her. We usually did.

Together, these were our cats, our babies, but no one ever told us about "staggering" your pets, so we lost them all within a year and a half of each other. We took a trip almost immediately because the idea of staying in a markedly empty apartment sounded appalling. When we came back, we told each other we'd get another cat someday. The ache of loss kept "someday" feeling far away, for a long time.

And then we met Carlitos. Originally a part of my mom's barely-in-control backyard colony of strays, Carlitos (called Guerito by Mom, because we love our diminutives) was easily the friendliest, most laid-back stray cat we'd ever met. He'd meow in appreciation (or sometimes impatience) at feeding time, smoothing his body against legs, and accepting head scritches happily. Sandy and I fell in love with him, and decided we'd adopt him.

It took a few months, partly because we had to get through other obligations first, and partly because we live in Chicago and Mom doesn't. Finally, we managed to get to El Paso with the express intent of bringing Carlitos home with us. I'll explain it in the same blurred, whirlwind way it seemed to happen to us:

Grab Carlitos and put him in a carrier. Take him to our old vet on the West Side, across town from Mom's neighborhood. Carlitos, stressed, meows and pants the whole way. The vet declares the cat healthy as a horse, and recommends a CBD tincture to calm him on the flight. Back to the house, where we put him in our bedroom so he can acclimate to us some more. (This works well.) A couple of days later we realize we looked at our flight plans wrong, and our plane leaves late that night instead of the next. Run around town to get an airline-approved carrier, CBD oil, a tag and collar. Administer the CDB oil, which doesn't seem to be working. Get to the airport, where they insist on having me taking Carlitos out of the carrier so they can scan it. We insist on a closed room. Carlitos get through it like a champ — a nervous champ, but still. Onto the airplane, which makes so much damn noise. But the CBD oil seems to be kicking in, and Carlitos only meows a few times during the three-hour flight. At O'Hare we get a Lyft (instead of taking the train/bus combo we usually use to get back and forth from the airport), and once home we keep Carlitos in his carrier while I run to the supermarket on the corner to get food, litter, and a box. Back at home, Carlitos is suspicious, but alternates between affectionate and staying out of sight. And now, it's six days later.

To be honest, we're a little stressed out about the way Carlitos is behaving so far, but we try to remind ourselves he has a lot of new things to get used to right now. He mostly hides away most of the day — first under our pillows, then crammed into a small space between the bed and the wall, and now in a bottom cubby of a wardrobe he figured out how to open — and will only come out for short periods before disappearing again. For the past two days he's refused to come out at all, manifesting only to eat and use his litter box after we've gone to bed, when the house is dark and quiet.

But that's OK. He's been a stray all his life. Hiding and sleeping during the day is a survival method he probably learned early. He had a routine he followed for years, and that's been upended. He had an entire backyard — probably a whole neighborhood — to roam, and now he's living in a small apartment. I'd be a little freaked out, too. Adjusting to change takes time.

So we know we just have to be patient. Eventually he'll poke his head out from behind my shirts and join us on the couch. He'll ignore the various noises that come with his new apartment, and he'll eat and sleep knowing he's safe, and loved. Someday he'll snuggle up to us, demanding scratches under his chin and long strokes over his ribcage. He'll purr, and look at us with his yellow eyes and Pink Panther face, and we'll fall more and more in love with him. And, someday, he'll break our hearts all over again.

But that'll be OK, too. We'll keep loving him anyway.

MOVING ON

If you know me at all, you probably know I think cancer is a real sonofabitch. A few days ago I found out podcasting pal Mike Gillis, co-host of Radio vs. the Martians, just had surgery following a diagnosis of testicular cancer. (If you know me a little better, you know I take testicular cancer personally.) Luckily, Mike's prognosis is good, and everyone moved quickly to get that fucker out and gone. So here's to Mike's continued recovery and good health, and some encouragement to give Radio vs. the Martians a listen if you haven't already — it's honestly one of my favorite podcasts.

It took remarkably little time to get out of the rhythm of writing this newsletter, so Screens/Sounds/Pages and Image of the Week will be back next week. In the meantime, here's another picture of my cat:

Yeah, we moved that dish as soon as we saw Carlitos could find his way to the top of the kitchen cabinets.

SHARING IS CARING

My podcasts — PlastiCast and The Mirror Factory — can proudly be found on The Fire and Water Podcast Network. I'm also a semi-frequent guest on other FW podcasts, and a search of my name will turn those up. There are a lot of great shows on the Network, so check 'em out.

On Twitter you can find me at my personal account, the Plastic Man account, and even at this one for The Mirror Factory. You can also follow me on Facebook and Instagram.